- Home

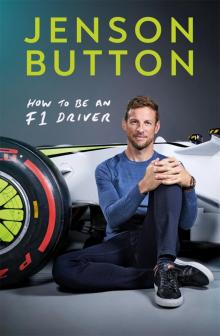

- Jenson Button

How to Be an F1 Driver

How to Be an F1 Driver Read online

Published by Blink Publishing

2.25, The Plaza,

535 Kings Road,

Chelsea Harbour,

London, SW10 0SZ

www.blinkpublishing.co.uk

facebook.com/blinkpublishing

twitter.com/blinkpublishing

Hardback – 978-1-788-702-61-4

Trade paperback – 978-1-788-702-62-1

Ebook – 978-1-788-702-63-8

All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or circulated in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing of the publisher.

A CIP catalogue of this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by seagulls.net

Copyright © Jenson Button, 2019

Jenson Button has asserted his moral right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them.

Blink Publishing is an imprint of Bonnier Books UK

www.bonnierbooks.co.uk

To the ‘new boy’, Hendrix.

I’m going to buy you a copy of How To Be A Doctor as well to balance things out.

CONTENTS

Driving Lessons

1. Don’t Call It A Comeback

2. Monaco

3. Being A Selfish Bastard (And Other Essential Skills)

4. Driving Like A Pro … Even When You’re A Beginner

5. How Not To Buy A Yacht (And Other Lifestyle Choices)

6. Doing The Job

7. Big Trucks

8. The Swag

9. Champagne Spraying Is All In The Thumb

10. Finding An Edge

11. How To Not Quite, Not Nearly, Win Le Mans

12. Faces And Places

13. The Perfect Lap

14. How To Be A Normal Joe

Acknowledgements

Index

DRIVING LESSONS

‘Right, Mr Burton,’ says the driving instructor, with the distinctive leathery purr of someone born and bred in Los Angeles.

‘It’s Button, actually,’ I correct him, settling in behind the wheel of the Honda Accord, ready for my lesson. ‘Jenson Button.’

‘Ginseng Button?’

I try again. ‘Jenson Button.’

‘Of course!’ he explodes. ‘It’s your English accent. Jenson Button. Jen-son But-ton. Right. Got it. Okay, Mr But-ton, so you’re here today so that we can get you up to speed on your LA driving ahead of your test, is that right?’

‘Yes,’ I reply.

What I’ve discovered since moving in with Brittny is that making my way around LA isn’t simply a case of staying on the right-hand side of the road and hoping for the best. There are tons of little things you need to know, like the fact that you’re permitted to turn right at a red stop light, or the odd way you have to deal with cycle lanes, and I need to know all this in order to get my Californian driving licence. It doesn’t matter where you’re from, or what you do for a living, you need a Californian driving licence if you want to use the roads.

In actual fact, it will turn out that I don’t really need to learn this stuff for the test when it eventually happens, because the test consists of me very nervously driving around Fontana for a bit, with the examiner saying, ‘It’s fifty here, it’s fifty, you can go faster,’ out of the side of her mouth, and then passing me on all aspects of the test apart from one – braking. I’d braked too late, apparently.

‘I didn’t brake too late,’ I will moan to Brittny afterwards.

‘You always brake too late,’ she responds, long-sufferingly.

But that’s to come. Right now, I just need to get the hang of the road systems in my adopted home of LA, and the best way of doing that is by having an actual driving lesson. On the one hand, this is uncharacteristically sensible of me. On the other hand, I still have the shame of failing my first UK driving test branded on my heart so I want to get it right. Besides, Britt’s dad is a Californian Highway Patrol officer so I need to keep my nose clean.

‘Okay, Mr But-ton, let’s try moving off, shall we?’ says the instructor. We get rolling and as we drive it occurs to me that this is only my fourth-ever driving lesson, and there’s been a twenty-year gap between this one and the first three, when my instructor was Roger Brunt, who used to race against my dad in autocross. It wasn’t Roger’s fault that I went on to fail. I was too cocky, that was my problem.

‘You’re doing well,’ the instructor assures me, before asking, ‘What is it that you do for a living, Mr But-ton?’

‘Actually, I’m a driver,’ I tell him.

He’s thinking. Pizza delivery? Uber? UPS?

‘A racing driver,’ I add, helpfully.

‘A racing driver? Wow,’ he says. He lapses into silence but when I steal a glance over at him I can see that he’s googling me.

‘Wow,’ he says at last, holding up the phone. ‘Is this you?’

‘Yeah,’ I say, ‘that’s me.’

He squints at the phone. ‘Says here that you’ve retired from Form-ula One. Is that right?’

‘Well…’ I say.

DON’T CALL IT A COMEBACK

Like the song goes, I heard it through the grapevine.

‘They’re going to call you.’

Various people telling me. They’re going to call you. Any day now. And I’d be standing by the side of my pool thinking, Bugger. Really? Maybe I should change my number…

The problem was that my last race in Formula One (or what I thought at the time would be my last race in Formula One) had been at Abu Dhabi in 2016 and it had been awesome. It wasn’t a great race – I’d retired with a broken right front suspension – but in many ways that didn’t matter, and probably even improved the situation, because it meant that I’d had my own little farewell before the end, without competing with the podium celebrations (which I would have overshadowed, obviously).

My team was all there, giving it the big goodbye: my friends and family, Brittny, the whole crew. It was a fantastic send-off and no better way to end 17 years in the game, a lifetime spent on planes, in motorhomes and being squeezed into the cockpits of cars. Yes, it was the stuff of boyhood dreams, and no way do I want to give the impression that I’m at all ungrateful about any of that because I spent those 17 years pinching myself at my good fortune, but…

There’s always a ‘but’. My father had died in 2014, and with him went some of me. Not my passion for racing, which as you’re about to find out, has never dimmed. But my taste for the life of Formula One. Without him the paddock hadn’t been quite the same. Not only that but I was mentally and physically exhausted – tired of what is, after all, a repetitious life. And there comes a time when, no matter how great it is, you want a break from that repetition. So I’d turned my back on F1 and decided to do something different for a while: take part in triathlons, do a bit of decorating. I wanted to enjoy the freedom from the various pressures of the sport: the teams, the teammates, the sponsors, the media, the whole brilliant but physically and emotionally exhausting merry-go-round of it all. For the first time in my adult life my home was more than a crash pad; I was starting to think of putting down roots, and in Brittny I’d met someone with whom I wanted to share that experience, who maybe was the catalyst for it all. I’d even earned my Californian driving licence, and I was shortly to be scratching my racing itch by competing in Super GT.

In other words, my ducks were in a row.

And

F1 did not feature.

Hey, I thought. Maybe the grapevine is wrong on this occasion. Perhaps the call will never come.

And then the phone went one morning and it was McLaren principal Eric Boullier, who told me that Fernando Alonso wanted to go off and drive the Indianapolis 500, which was taking place on the very same day as the 2017 Monaco Grand Prix, which meant that…

‘I want you to come and race at Monaco in May.’

It was the beginning of April, so I was like, ‘But I haven’t driven the car. I haven’t done any racing since November last year. I’ve been out here training for triathlons and decorating. If you need advice on what shade to paint your wall, I’m your man, but chucking me in at Monaco…?’

The thing is that as a racing driver, it doesn’t matter what you drive, you want to be prepared because you still care what people think, and I was well aware that the season had featured one of the sport’s biggest-ever rule changes. The car would be a completely different animal. Not just a new chassis but bigger tyres, heavier, wider, and with more downforce.

‘You’re the reserve driver,’ Eric pointed out in the face of my obvious reluctance, ‘this is your job.’

‘Oh okay. Um, let me have a think.’

I was stalling. Eric and I both knew that I was contractually obliged to drive. Even so, I looked at my pool. I thought about Brittny, who was pottering about in the house somewhere, and I called Richard Goddard, my manager. ‘Can I get out of this?’

He cleared his throat. ‘Well, not really, no. I mean, they’re paying you a lot of money to basically do nothing this year apart from be on call in case they need you.’

‘Yeah, but I didn’t think they’d need me.’

‘Well, they do, Jenson. They want you to drive their Formula One car in probably the world’s most prestigious Grand Prix. Hard life, isn’t it?’

Richard knows about as much about being a racing driver as I know about managing racing drivers. Which is to say, quite a lot, actually, and certainly much more than the ordinary Joe. But still not the full enchilada. What’s it like to sit behind the wheel of a racing car? How does it feel to be a part of the Grand Prix circus? The kit, the clobber? The rituals, rules and rivalries? How to take a corner, how to run a motorhome and why you should never, under any circumstance, buy a yacht.

All the stuff you’re about to find out, in fact – assuming you read on.

Anyway. I got the picture, ended the call and had a quick word with myself. A couple of minutes was all it took, and when I rang back it was with a revised approach. ‘Cheers, Eric,’ I said, ‘I’m really excited to be racing for you again.’

And I meant it, I really did, because my philosophy in life is that when you set out to do something, whatever it is, you have to do it properly.

Especially when you’re contractually obliged to do so.

MONACO

Years ago, when Lewis was my teammate at McLaren, the two of us did voiceovers for an animated series called Tooned in which we played ourselves. It was my second foray into the world of quality drama after an Oscar-winning Head & Shoulders ad I did in 2011, and I thought it was pretty good, actually, and certainly something to show the kids one day.

Anyway, Tooned featured a large underground track that the cartoon Lewis and I used for practice, and because of that a lot of people assumed that such a thing really existed at McLaren HQ in Woking.

Reality flash: it didn’t.

What we did have, however, was a simulator – and that became my home for two days prior to the race. Actually, the car felt all right. I began to wonder if I was worrying about nothing. True, I rolled it into the harbour. Twice. But I reassured myself that it couldn’t happen in real life thanks to the barriers, and felt that the overall experience was pretty positive.

Next thing you know, I was arriving at the circuit. Like Hannibal in The A-Team, I had assembled my old crew – and I didn’t even have to disguise myself as ‘Mr Lee, the dry cleaner’. With me came Brittny, Richard, my physio Mikey, my best mate Chrissy Buncombe, my PR guy James Williamson – all the old faces.

Even so, walking into the paddock was strange. What struck me was a sense that things were unchanged, but at the same time had moved on. And there was something else, too: I felt no pressure. Well, I did. But it was all self-inflicted. As for external pressure? None. Everyone was all like, ‘He’s had seven months out of a car; he’s never even driven these new ones. You can’t expect him to be as good as he was.’

And despite that – or maybe even because of it – I found myself wondering, Just a minute. How well could things go here? After all, this was Monaco, a circuit I knew like the back of my hand, a mostly happy hunting ground over the 16 times I’d raced there. Yes, it was the scene of my worst accident (practice, 2003, a 185mph crash that earned me an overnight stay in hospital), but it was also the venue for one of my best-ever laps (2009, a qualifying lap for Brawn that put me on pole, from which I went on to win the race).

Added to all that, I used to live there, so it was virtually a home race for me.

So I started to dream. Not big. I’m no fool. It’s not like I was thinking podium. But I hoped to finish in the top ten; I hoped to beat my teammate, Stoffel Vandoorne; and I hoped to be able to score the team’s first points of the season.

Practice one came round and they started it up. I swallowed, riding the weirdest sensation that washed over me. A feeling of being like an alien in this car, that lasted as I dropped the clutch to pull out of the garage, going down the pit lane, watching the speed limiter and working out where all the buttons were on the steering wheel, all of which were so different from what I was used to.

I went out. The first corner is in the pit lane still, and then you go up the hill and then to Casino Square, by which time I just about had the hang of it. I remember going through Casino Square with the biggest smile on my face, because all of a sudden it felt so normal, so natural, and I was, like, Are you kidding me? This is seven months off. It’s a completely different car. And yet it all felt so normal to me. So brilliant.

By the end of the lap I felt full of renewed confidence that while things had moved on, they hadn’t moved that far. It was still a car. It still had four wheels touching the road, and the steering wheel in my hands did what it always used to do.

Saturday. Qualifying. I was feeling good, and Q1 went well, in the sense that I was comfortably through into Q2 and feeling happy with the car. My confidence in it was growing and although I was still missing a bit on braking I was certain I could gain more. What’s more, I knew I’d left a bit out there on the circuit. In other words, there was still room for improvement.

My next lap didn’t start too well. Bit of a braking SNAFU on turn one. But it didn’t matter, because by the time I’d taken the little drag up the hill, it was ancient history and I was back to absolutely loving the drive, a huge grin stitched on my face as I eased it through Casino, getting the maximum out of it at last, touching the barrier a tiny bit on the way out, correcting a hint of oversteer. For the rest of what was a blissful lap I felt that I almost – almost – had the measure of the car.

‘You’re P9,’ they told me at the end of it. ‘You’ve qualified into Q3.’

Which was like pole position for me. I was on cloud nine.

What’s more, I’d beaten Stoffel, my teammate, who had qualified tenth, and in Formula One the only real test of your individual strength as a driver is whether or not you can beat your teammate.

Two hours later I came back down to earth with a thump that must have registered on the Richter scale.

‘We’ve got a problem.’

‘What problem?’

‘A problem with the engine. We’re going to have to change it.’

‘Meaning?’

‘You’ll have to start from the pit lane. So you’re last.’

I was like, ‘Did you know that this might happen?’

They cleared their throats and looked at their shoes. ‘Yeah, w

e just didn’t want to tell you before qualifying.’

I thought about it and climbed down from the ceiling, deciding that they’d probably done the right thing, because if I’d known about the possible engine problem then I probably wouldn’t have performed so well and I’d have got nothing out of the weekend.

But yes, it hurt, especially as it was only my car, and Stoffel moved up to ninth as result, leaving me staring down the barrel of a Sunday race that was not going to be fun in the slightest.

And boy, was I right about that.

I woke up the next morning grimly contemplating a day of driving around Monaco for two hours being lapped – and nothing that anybody said could cheer me up.

Sure enough, as the race proceeded and a change of pit-stop strategy came to nothing, I sat there simmering, with Pascal Wehrlein in front of me – until, 50 laps into the 72-lap race, I could take it no more and spoke to my engineer. ‘Can we just pit again, put new tyres on and then we’ll see if we can catch and overtake Wehrlein?’

What did we have to lose? Monaco is terrible for overtakes – an average of 12 per race compared to 52 for somewhere like Shanghai. But that’s still 12 overtakes, and there was no reason I couldn’t be one of them.

Yes, they said. So I pitted, we put on another set of tyres and I set off again. The pace was good, especially when I was in clear air, and pretty soon I found myself going from being 20 seconds behind Wehrlein to catching him up – until I was right on his tail and thinking about making my move.

Again, what did I have to lose? If it worked it would be a great move. If it didn’t, we’d crash, I’d hit the bar early and drink lots of beer.

It was just before the tunnel, the double right-hander. I came up alongside him on the inside. No one really overtakes there, but I was feeling pretty gung-ho and thought I’d have a go. To be fair, if he’d seen me, it would have been okay. It’s just that…

He didn’t.

And by the time I realised that he wasn’t aware of me it was too late because he was already turning in, and we touched. Ding. As we did that, I braked, so my car went backwards, his shot forward, our tyres clashed – and that was enough to flip him over onto his side against the barrier.

How to Be an F1 Driver

How to Be an F1 Driver