- Home

- Jenson Button

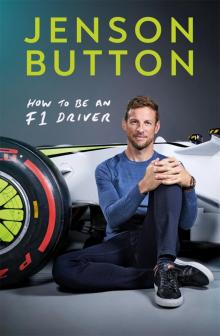

How to Be an F1 Driver Page 2

How to Be an F1 Driver Read online

Page 2

Wehrlein had hurt his spine in a crash earlier that year, so I was worried about him. I couldn’t see anything because the floor of his car was blocking my view, but I was close enough to know that his head was against the tyre wall. All I could do was pull away from his upturned car and make my way through the tunnel, creating more sparks than a welder on a deadline before pulling off the right-hand side at the other end.

As I got out of the car I heard that Wehrlein had clambered out of his Sauber unharmed, so at least he was okay. Probably cursing me, mind you. The accident was more my fault than his: 60/40, I’d say.

As for me, I had to do the walk of shame back to the paddock, the boats in the harbour on one side, the grandstands on the other, the crowd being kind enough to clap and wave as I trudged dejectedly past, even though they were probably thinking, Look at him. What a wanker. He’s just crashed when he was in last place.

And still my day’s woes were yet to end. Monaco is the only circuit where the paddock and the pit lane are in completely different places, and I reached the garages first. There I discovered that Stoffel had been running in tenth, and thus had been about to score the team’s first point of the season. The mechanics had been levitating with excitement at the thought of scoring a point at last. But because of my little incident the safety car had gone out, which meant that all the cars had bunched up, and they were all on newer tyres than Stoffel, and so…

Well, in the end he hit the wall after being tipped off the track by Sergio Pérez, but I could tell they were pissed off at me. It was the little giveaways that did it. Like the way they looked at me, shook their heads and then threw their gloves on the floor.

I felt bad for them (while at the same time thinking, For goodness sake, it’s only a point. This is a team that should be fighting for the World Championship) and left them to it, onto the second leg of my journey back to the paddock, interviews all the way down – can’t say I was at my most gracious – until I got to the engineers. ‘Sorry guys.’

‘Don’t worry,’ they said, ‘it happens. We shouldn’t have put you in that position of starting last.’ And then, when I saw the mechanics again after the race, they’d cooled down and I gave them all a hug and apologised, and they were, like, ‘It’s cool, it is what it is,’ just that they were upset because that they’d lost a point, which would have been the first point of the season.

Except – what am I saying? As it turned out, I did in fact get two points out of that race.

I got two penalty points on my super licence for flipping Pascal Wehrlein against the tyre wall.

BEING A SELFISH BASTARD

(AND OTHER ESSENTIAL SKILLS)

My Monaco return wasn’t a great day at the office, but there were upsides. Two upsides, in fact: first, I proved to myself that I could still drive bloody fast in an F1 car; second, the very act of going back became a way of checking whether I’d made the right decision to retire in the first place. After a boozy Sunday night I left on Monday morning with a hangover and the sure knowledge that I’d made the right call.

Yes, it had been nice to see the old faces again, but being back in the spotlight had reminded me how insular it was. How you never got off the plane and thought, ‘Wow, this is someplace new’, because the instant you arrived you were absorbed into the city that is Formulaoneville and it was the same city wherever you went in the world. Airport, hotel, circuit, back to the hotel, and that’s it. You don’t see anything else.

Wait. Don’t get me wrong here. I’m talking about being a driver. As a spectator my love for the sport has never diminished, and if Monaco reaffirmed my decision to leave F1, it also reaffirmed my love of racing as a whole, something that’s been in me since I was yea big. I won’t go into the details of how I became a racing driver (there’s another book for that), but mine was a path trodden by the likes of Ayrton Senna and Johnny Herbert; it took me through the ranks of junior karting and into Formula One, and it was a journey started by my father.

I’ll be a dad myself by the time you read this and if my son, Hendrix Jonathan Button, wants to go racing then just you try and stop us. We’ll be off for some important father–son bonding time: karting, probably, but not exclusively, because it’s important to do all kinds of driving, not just the stuff that you like. You need to learn how to drive different vehicles, how they behave in varying conditions, how to brake, how to handle a circuit, how to slide, even going over jumps. It’s all about building up general driving skill.

Me, I got my first go-kart when I was seven, mainly for something to do at the weekends because my parents had split up. My dad was great. He wasn’t one of those tyrants I used to see shouting at their kids. I realise now the benefit of starting young. You’re like a sponge, soaking up knowledge, learning at an age when it all goes in. But what’s just as important is making sure it starts off being fun and stays that way, because if you’re too focused and it becomes all-consuming then the chances are you’ll hate it by the time you’re 12.

I couldn’t improve on the way that my dad it. He’d always say, ‘If you’re not enjoying it, or you want to take a break, tell me, and we’ll stop.’ We never did, of course.

TWELVE ESSENTIAL TOOLS IN A DRIVER’S TOOLKIT

1. Natural skill

Ask me what is ‘natural skill’ and I’ll look at you as though you’re a bit hard of thinking and say something like, ‘Well, it’s skill, isn’t it? Only skill that you already have,’ and maybe I’ll remember first getting into a kart all those years ago. How I just somehow knew what to do.

And I bet that every single driver on the grid of a Grand Prix had a similar experience, because the fact is that all drivers in Formula One have natural talent, just that some have more of it than others.

Lewis has oodles of it, for example. Put him in anything and he’ll be quick. Then there are other drivers who have a natural gift but whose talent isn’t quite as abundant as his and so have to work at it. Fernando Alonso is a good example, who has worked hard to improve his skills, working on any areas of weakness and to make certain that he can get the maximum out of the car and out of the team. If you ask me, Fernando is a good example of a complete driver because he understands how to supplement his natural ability with hard work.

And of course it’s in your genes, somehow. Take a bow, Max Verstappen, whose father, Jos, was an F1 driver, and whose mother, Sophie Kumpen, was also a racing driver (she was my teammate in karting and she was so quick). Clearly, there’s no doubt Max has inherited his parents’ talent. Just look at the way that he can push a car in wet conditions. A great race for him was Brazil 2016, my second-to-last Grand Prix. It was wet but it was just unreal what Max could do with the car that most of the other drivers couldn’t. I mean, he almost hit the wall and hurt himself badly, but he didn’t. He kept it out there, and he had a great race. That’s natural. That’s not learnt.

For any driver, though, natural talent is not enough. Eventually, and providing that lady luck continues to smile on you with a full-faced idiot grin you’ll be combining your God-given skill with experience, which is when you get to be a really deadly competitor, but you’ll also need to be a grafter. A lot of drivers think they can skip that bit. A lot of drivers, especially when they first join the circus, will think being quick is enough.

Me, for example. Coming into Formula One in 2000 I believed my raw talent was enough. I was 20 years old, racing with Williams, a multiple World Championship winning team. That season I qualified third at Spa, which is one of the most difficult tracks in the world. I thought I was the mutt’s nuts.

And then in 2001 the results stopped coming. Racing with Benetton, I was uncompetitive and outraced by my teammate, Giancarlo Fisichella, added to which I was maybe enjoying the trappings of wealth a bit too much.

I’ll touch on this again later, but it was the team who brought me out of that dark place. They told me, ‘You’re quick, but you think it’s easy. You think your driving skill is enough, but it’s not.’ They m

ade me work harder, and after that I never stopped putting in the time and effort. I spent more time with the engineers than I did with my mates; more time in the garage than I did on yachts – and it paid off.

In brief: No matter how much talent you (think you) have, you need to supplement it with hard graft. Which brings me on to...

2. A burning desire to learn

Coming from karting to F1 was a big shock, because karting is the opposite of racing an F1 car. There’s no power in a kart. Lots of grip, but no power. So it’s just about being as smooth as possible. Some of that smoothness you carry across to Formula One – not being aggressive on the steering wheel, for example – but other things, like braking, you don’t, because even though you’ve acquired race-craft and driving skills in karting, it’s just a fraction of the learning needed to be at the top of your game in an F1 car – and if you can’t adapt it could be the end of your career. If you come in and you’re not quick enough or you make too many mistakes, you’re out immediately. Remember Yuji Ide? Exactly.

Kevin Magnussen was my teammate in 2014. He’d won everything before he got to F1, and he thought he’d come into the sport, destroy his teammate (me) and be winning races. And he wasn’t, of course, because he made the classic mistake that we all make of thinking that he was the finished article.

I remember him in the third race of the year saying to me, ‘JB, I didn’t realise how tough this was. How much I’d have to work.’

‘Aha, Kevin,’ I said, ‘and that’s because you’re racing against the very best in the world, the crème de la crème – chaps who have so much experience, not just of racing, but also of setting up of a Formula One car. You should be learning as a racing driver, Kevin, especially when you get to a sport that’s as complex as Formula One.’

I mean, maybe that’s not an exact quote. But it was something just as articulate and wise as that.

In brief: It’s important to have confidence in your ability, but also have the understanding that you need to learn, you should always be learning, you’re never as good as you should be, you’re never the greatest. In other words, never think you’re the best – but strive to be.

3. The ability to be a selfish bastard

Sweeping statement alert: it’s almost impossible to hold down a relationship and be a Formula One driver. It was Brittny, in the early days of our relationship, who pointed this out to me, probably as I was shouldering my bag and leaving to catch a flight. And while in the bad old days I might well have told her she was plain wrong, these days I’m old and ugly enough to realise that she was in fact totally on the money: I was very selfish, and, having bailed from F1, I’m a very different person now. I try to be kind and generous to a fault. And by the way, your hair really suits you like that.

Take Nico Rosberg, who won the World Championship in 2016 and then quit the sport. There were those who said that he’d bailed because he’d won the World Championship, that he was lucky and he knew Lewis would beat him next year.

I know there were those who said that, because I was one of them.

However, I’ve since heard him say something that resonated with me. He said, ‘Sure, I could have gone on, trying to defend the title. But why? It’s easy to want more, more, more, but you also have to be careful and not lose yourself as a person.’

I respect that and understand how he felt. Plus it was interesting to hear him say that, because not only had I never heard a driver say that before but because I’ve always felt like that myself: you have to forget about everything else in life and become a person that you might not like. You have to be very selfish.

There is, of course, a positive aspect to being selfish (having spent years at it I had to find something good) and it’s the fact that you’re focused on what you’re doing, being in the right frame of mind, being as fit as possible, being ready for the start of the year. You also have to make sure that you get on well with the team and the sponsors, and though that sounds like the opposite of being selfish – quite nice of you, in fact – it’s actually all about improving your standing and getting the best out of those around you so they’ll work harder for you, and thus your competitiveness will improve. So, yeah, it’s still pretty selfish.

In brief: In F1, everything is a selfish act until you stop being a driver, and then it’s not.

4. A competitive nature

Am I competitive? Much more competitive than you, I bet.

And this is a terrible thing to admit, but I don’t tend to compete at things that I can’t win, which is one of the reasons I don’t play any other sports. Here in LA I’ve taken up boxing and lifting weights, both things I’d never done and didn’t want to do until Brittny badgered me into it. I love them both now, but only since I got good.

But I’m the same with anything. Like, if I do my shoelaces up and it takes longer than I think it should, that annoys me. Or, I don’t know, measuring coffee beans for grinding and it’s not 15 grams – or it is 15 grams, but I didn’t do it as quickly as I did it the day before. Stuff like that. Stupid stuff.

And here’s another sad thing to admit: if I hadn’t been any good at racing I wouldn’t have continued with it. I couldn’t have stood people thinking, You’re not good enough, and, worse, knowing it in my own heart. I’d have had to do something else – something else that channelled my competitive spirit.

In brief: If you’re not super-competitive you’re probably not cut out for sports. I mean: duh.

5. A team-player disposition

Despite Formula One’s reputation for breeding prima donnas, there is in fact no room for them because F1 is a team sport, pure and simple.

Not that it was always the case, mind you, and it’s taken teams and drivers a while to wake up to the fact that the most successful teams are the ones who work well together, which means that these days, drivers are spending more time at the factory. They’ve realised that they have to hang out with the engineers to understand the cars, because people who came before them have done it and achieved great things – drivers like myself and Fernando and Sebastian Vettel – drivers who put the time and effort in.

So now when a new driver comes in, the team says to them, ‘You need to spend time with the engineer; you need to understand the car,’ as well as spending a lot of time in simulators, which I never had when I was a kid. It was Gran Turismo, that was it. Or Mario Kart.

All this means that they’re spending much more time understanding what the car can and can’t do, they’re a lot more prepared than they – by which I mean ‘we’ – used to be, and as a result they get into F1 cars and can be pretty quick straight away.

But there’s a drawback. Kids who have spent a lot of time in simulators and not enough time on the track are in danger of suffering a huge setback when they crash. It knocks the stuffing out of them. A computer game helps you in many ways, but it doesn’t help you understand how an impact feels, and we all have to crash one time in our lives to understand what G-force feels like – proper G-force, I’m talking 35G. It puts you in your place a little bit and you respect the car and the circuits a little bit more as a result.

We’ll talk more about the simulator in a bit. The point being that young drivers are absorbed into a team-player culture quicker these days than ever before, and they understand that they’re not driving for themselves, they’re doing it for the team.

So when, for example, you crash the car, you’re devastated. Not for yourself, you don’t give a shit about yourself, but for the mechanics, all those guys who have worked flat out to build the car, who’ve now got to stay up all night – because they do, you know – and do it all again.

They’re the guys for whom you reserve your sympathy and your apologies; they’re the first people you see when you come in after you’ve stacked the car up against the wall. Not the team boss. You’ll speak to him or her last. You walk around every single mechanic and you say sorry. Most of the time the mechanics will pat you on the back and say, ‘Shit happens, ma

te, it’s great that you were pushing,’ And then and only then will you speak to the team boss. But that bit doesn’t matter so much; you don’t mind about that, that’s just a ‘sorry for crashing your car’, which he should be all right about, because for him it’s just a case of finding money in the budget, which – this being Formula One – he should be able to do with comparative ease.

After that you might even spend time in the garage with the mechanics when they’re rebuilding. If you see drivers rolling their sleeves up and getting busy with a wrench then it’s probably just for TV: the moment the cameras leave the mechanics are snatching the tools out of the driver’s hand and shooing them off to a safe distance before they can do any damage. Even so, the mechanics like drivers to be there. They want you to see and appreciate the amount of work that’s going into this extraordinary piece of kit.

Even when they’re not working on the car, it’s worth spending a bit of time with them. You’ll never be a fully paid-up member of their gang – mechanics are a breed unto themselves, the garage a closed society – but you can learn from them and they can learn from you. Day to day they’ll hear you shouting at your engineer but they rarely hear first-hand what you have to say about the car or what you think about the team, and I think they deserve to hear it.

I’d often go out for a booze-up with my engineers and mechanics post-race. They’d have a few beers, say what they really thought, and sometimes it wasn’t especially flattering. ‘I thought you were a bit of a dick at such-and-such a time.’ And more often than not they’d be right about that.

How to Be an F1 Driver

How to Be an F1 Driver